Home » Your Local Area » Snowy Valleys

Local Profile for Snowy Valleys Council

Snowy Valleys Local Government Area

Hazard Exposure Summary

Climate Change Data Summary

Risk Exposure Summary

Reference

Snowy Valleys Council is bounded by Cottamundra-Gundagai Regional Council and Yass Valley Council in the north, an Unincorporated New South Wales in the east, Snowy Monaro Regional Council, Murray River, the Victorian border and Towong Shire in the south, and Greater Hume Shire and Wagga Wagga City in the west.

The Council area is situated in the Riverina Murray region of New South Wales and the original inhabitants of the Snowy Valley were the various tribes of the Wiradjuri people. ¹

The Region has an ageing population, which is set to increase. The Council area is rich in history and culture, with the area’s origins in grazing, gold mining and timber production. Traversing the Council area is the Snowy Mountains Highway which connects in with Cooma to the east and joins with the Hume Highway in the north.

The Snowy Valley Region includes the township of Tumut which the administrative centre of the Region. Other major townships in the Region include Adeling, Batlow, and Tumbarumba. ²

The Snowy Valleys region is predominately rural land that is largely used for agriculture, mostly beef cattle and timber production. Other key industries to the area’s economy include sheep grazing, paper stationary and other converted paper manufacturing, fruit growing and power generation. Much of the community works in either the timber or agricultural industries, with many others working in jobs which provide support for these major industries . Tourism is also considered to be an important industry to the region given the proximity to national parks, major snowfields and natural landscapes. ³

Socio-Demographic Profile

In 2024, the estimated residential population of Snowy Valleys Council was 14,955 people. ⁴

In 2021, based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2021 census data, the Snowy Valleys Region

- LGA size – 8,958km2; ⁵

- Population – 14,901; ⁶

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population – 6.3% (942 persons); ⁷

- No of properties/dwellings – 7,076; ⁸

- Persons aged under 5 – 5.6% (827 persons); ⁹

- Persons aged over 65 – 23.21% (3,459 persons); 10

- Persons with disability – 6.1% (909 persons); 11

- No of new residents from overseas (2016 – 2021) – 189 people; 12

- Persons culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) / non English speaking at home – 4.4% (649 persons); and 13

- Top 5 languages spoken at home are Afrikaans, Filipino/Tagalog, Mandarin, Thai, German. 14

Economic Profile

Of the approximately 896,000 hectares of land in the Snowy Valleys LGA, 236,493 hectares of land (or slightly over a quarter of the entire land area) is used for agricultural purposes. In 2021, the total gross value of agricultural production was $198.3 million), with livestock slaughtered and other disposals comprising $114.4 million, and cropping comprises of $59.9 million. 15

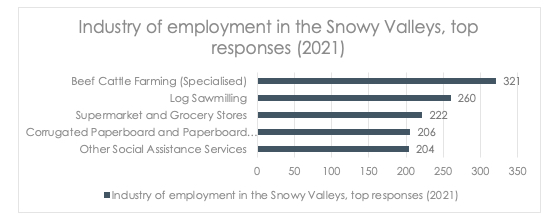

The Snowy Valleys supports 6,549 jobs locally (the primary employment sectors are outlined in Figure 1 below. In summary Beef Cattle Farming (Specialised) is the largest industry of employment (321 people or 4.9%). Log Sawmilling employed 260 people (4%), and Supermarkets and Grocery Stores employed 222 people (3.4%). 16

Figure 1: Industry of Employment in the Snowy Valleys (2021) (Source: 2021 Census) 17

In 2020, despite significant shocks to the Snowy Valley Region’s key industries) there has been continued economic growth: 18

- Forestry – $92 million Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2020

- Manufacturing – $150 million GVA in 2020

- Tourism – $91 million visitor spend in 2021;

- Agriculture (sheep, grains and cattle) – $76 million GVA in 2020.

Environmental Profile

The Snowy Valleys area is located at high elevation and situated at the western foothills of the Snowy Mountains, bordered by Kosciusko National Park and the Murray River. The area acts as western gateway providing access to major snowfields in Kosciusko National Park and is recognised as one of the 167 worlds of biodiversity by the World Conservation Union. 19

Of the approximately 8,960 square kilometres of land, approximately 4,100 square kilometres is within National Parks (~45% of land in the Region) and 1,534 square kilometres is covered by state forests. The Snowy Valleys area has approximately 75% bushland and 23% grassland with the balance being the built environment or water bodies. 20

The waterways traversing the Snowy Valleys area form an important part of the Murray-Darling basin, with the Tumut River originating in the Snowy Mountains. This river is joined by two tributaries before meeting the Murrumbidgee catchment near Gundagai. The natural flow of this river is high while draining due to the snowmelt and other runoff from large sections of the Snowy Mountains regardless of being a relatively short river. The natural flow of the river is further aided by water transferred from the Tooma River and Lake Eucumbene through the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

The Burra Creek is also part of the Murrumbidgee catachment within the Murray-Darling basin and originates from the slopes of the Ginendoe Hill. The town of Tumbarumba is largely supplied with water from this creek and the creek will maintain a continuous flow of water in parts of its stream bed all year around.

The main land use for the Snowy Valleys is nature conservation. This is followed by grazing, forestry and cropping. 21

Governance Profile

Snowy Valleys Council is bounded by Cottamundra-Gundagai Regional Council and Yass Valley Council in the north, an Unincorporated New South Wales in the east, Snowy Monaro Regional Council, Murray River, the Victorian border and Towong Shire in the south, and Greater Hume Shire and Wagga Wagga City in the west.

The Council area is situated in the Riverina Murray region of New South Wales and the original inhabitants of the Snowy Valley were the various tribes of the Wiradjuri people. 22

The Council has nine elected Councillors for four-year term. The Mayor is elected by the Councillors and is recognised as the civic leader of the community. 23

The Snowy Valley Region includes the township of Tumut which the administrative centre of the Region. Other major townships in the Region include Adeling, Batlow, and Tumbarumba. 24

Hazard Exposure Summary

The LGA is vulnerable to a wide range of natural hazards, making it essential to understand the nature and extent of exposure to people, buildings, infrastructure, services, or natural resources to effectively assess and address associated risks.

Exposure can be seen in various forms:

- Relative exposure is a function of hazard, describing the frequency and magnitude of natural hazard events and capturing the compounding effect of multiple hazards (fire and flood for this analysis). Where a community is subject to both fire and flood, it is potentially less resilient than one exposed to a single hazard of the same frequency and magnitude;

- The physical exposure of a community is determined such that the quantum of exposed people, buildings, essential facilities, industry, and agriculture can be evaluated. The physical vulnerability of exposed elements is also important, such as the age and construction type of buildings (for example, buildings with raised floors are more resilient to flood as they provide greater protection to the occupants and their belongings, resulting in less loss of life and property); and

- Social vulnerability is determined by examining socio-economic and demographic factors that may exacerbate or ameliorate the effects of an external threat to a person’s life, livelihood, or assets. Examples of these types of indicators include age, occupation, health status, income and education.

The Resilience Blueprint identified the following hazards as relevant hazardous events for the southeast NSW region. In 2024 the State Disaster Mitigation Plan (SDMP) was implemented and any additional hazards or information regarding exposure of hazard in the region has been included below:

Fire (bushfire and grassfire)

Fire (bushfire and grassfire)

- Bush and grass fires are known to affect the Snowy Valley Region, with much of the rural areas identified as being within very high / high risk land;

- North-westerly winds accompanied by high day time temperatures with low humidity are associated with the bush fire season in the Snowy Valleys Region.

- The Snowy Valley Region has on average 66 bush fires per year, of which 4 on average can be considered to be significant; 25

- Based on the potential event probability, as provided by Risk Frontiers, annual average loss of residential, commercial and industrial buildings from flood in the LGA is 14 per cent under a RCP 4.5 scenario. This accounts for a low probability of occurring but a high financial cost consequence of bushfire activity;

- In 1965, a major bushfire burnt through much of the Tumut Valley (approximately 80,000 hectares; and

- In the 2019-20 bushfire season, the Region was significantly impacted by two major bushfire events. The Dunn’s Road Fire and The Green’s Valley Fire joined to create one ‘mega’ fire. The fire burnt through 402,650ha of land over 50 days, or the equivalent of 45% of the LGA. As a result, almost 250 houses were damaged or destroyed, and nearly 800 outbuildings were also damaged or destroyed. There was also one fatality and 12 injuries (three serious and nine minor). 26

Actions taken or proposed:

- Council’s Local Strategic Planning Statement (LSPS) considered risks associated with bushfires as a major issue affecting much of the Snowy Valleys Region. Planning Priority 3 of the LSPS is to ‘adapt to the impacts of hazards and climate change’.

- In the wake of the bushfires in 2020, Council has also undertaken various recovery efforts in the Region.

Flooding

Flooding

- Based on the potential event probability, as provided by Risk Frontiers, annual average loss of residential, commercial and industrial buildings from flood in the LGA is 7 per cent under a RCP 4.5 scenario. This accounts for a very low probability of occurring but a high financial cost consequence of flood activity;

- In Adelong, at the 1% AEP level of flooding under ideal flow conditions, 61 residential and 15 commercial/industrial properties would be flood affected (i.e. water has entered the allotment). The total flood damages at Adelong would amount to $0.87 Million in the event of a 1% AEP flood; 27

- Major flooding has occurred in Tumut previously, arising from Mcfarlanes Creek and the Tumut River. In early-March 2012, the Tumut River reached a major flood peak of 3.7 metres and several people and horses had to be rescued. The water came from the Goobarragandra River, which had 80 millimetres of rain yesterday; 28

- Major floods have occurred in the Tumbarumba area in 1891, 1903, 1905, 1931, 1960, 1974. More recently flooding has occurred in Tumbarumba:

- In October 2010, 98 properties near Tumbarumba were evacuated as a wall of the nearby Mannus Dam threatened to collapse; 29

- In 2020, a flash flood hit Tumbarumba. Reportedly there was significant flooding around the sports field, caravan park and around Hampton Avenue; and 30

- In November 2021. As a result of November 2021 flood, a walking bridge across Tumbarumba Creek was washed away. A home also had to be evacuated. 31

Actions taken or proposed:

- Council’s Local Strategic Planning Statement (LSPS) considered risks associated with flooding as a major issue affecting much of the Snowy Valleys Region. Planning Priority 3 of the LSPS is to ‘adapt to the impacts of hazards and climate change’. The LSPS proposed various actions to address the risk of flooding in the Region, including: 32

- Action 30: Identify studies and data required to address gaps and/or limitations and improve knowledge and management of flood risk including climate change (short term and ongoing); and

- Action 31: Undertake priority studies and management plans to address gaps in knowledge or management of flood risk and fulfil flood risk management responsibilities in accordance with the NSW Flood Prone Land Policy.

- Council have completed the Adelong Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan – Report in 2018. The Plan also identifies several actions for Council to better improve resilience to flooding in the Adelong floodplain; and 33

- Council has commenced preparing flood studies for Brungle, Tumut and Tumbarumba. Council undertook community consultation to obtain information on the impacts of previous flood events like March 2012, February 2019, January 2022, October 2022 and November 2022, as well as any earlier floods events. 34 35 36

Severe storm

Severe storm

- Severe storms in NSW are often associated with East Coast Lows (ECL). ECL events are extreme weather systems that occur in South-East Australia, bringing extreme winds, rain, hail and lightening;

- The maximum annual windspeed is projected to increase across the Snowy Valley Region in future;

- Dry lightening storms (generally occurring in late spring and summer) occur frequently and a major cause of bushfire ignition in the Region;

- On 25 November 2024, a severe storm impacted the Region leading to a natural disaster event being declared; 37

- In 2021 as a result of a severe storm, torrential rain in February 2021 led to further flooding events around Adelong and Tumbarumba. June 2021 saw the largest rainfall event in a single day since 2012 which caused localised flooding in many parts of the region, in particularly on the Tumut plains; 38

- Based on the potential event probability, as provided by Risk Frontiers, annual average loss of residential, commercial and industrial buildings from hail damage associated with a storm in the LGA is 54 per cent under a RCP 4.5 scenario. This accounts for a high probability of occurring and a high financial cost consequence of severe storm activity;

- Severe storms (with accompanying lightening, hail, wind snow and / or rain causing severe damage (including tornado) is identified as a likely natural hazard event in the South East Region EMPLAN; and

- In 2011, a severe hailstorm hit Batlow, an apple-growing region, leading to a disaster declaration. The storm stropped trees and damaged fruit with reported losses of 100 per cent in some of the 30 affected orchards. 39

Actions taken or proposed:

- No actions have been taken or proposed to address severe storm risks by Council.

Landslide

Landslide

- Landslide can be triggered by severe weather events (e.g. heavy rainfall) or human activities (vegetation removal, overgrazing, slope modification, etc.).40

- The probability of landslides in the region are considered rare, but the level of consequence can be high depending on the location. This risk is higher in parts of the LGA with steep topography.

Actions taken or proposed:

- No actions have been taken or proposed to address landslide risks by Council.

Heatwave

Heatwave

- A heatwave is generally defined as ‘a period of abnormally hot weather lasting over several days’, and can be characterised as three or more days of high maximum and high minimum temperatures that are unusual for that location’; and 41

![]() Tsunami

Tsunami

- Tsunami’s can be generated by a number of causes, however, undersea earthquakes are the most likely to generate such an event. Tsunami waves can run up beyond the high tide mark causing significant damage to coastal areas.

Note: The Snowy Monaro Region is not exposed to this hazard, however tsunami’s are a hazard for wider South East NSW Region and may have consequential impacts to the Region.

Actions taken or proposed:

- No actions have been taken or proposed for to address storm and cyclone risks by Council within the Region.

Earthquake

Earthquake

- The Canberra Region sits on a major eastern fault line. The nearest seismic zone is to the north near the township of Gunning. On 15 February 1998, a magnitude ML 4.2 earthquake occurred in the Brindabella Mountains, near Brindabella Homestead (in the north east of the Region), this earthquake was large enough that it was felt in Cooma; and 42

- Based on the potential event probability, as provided by Risk Frontiers, annual average loss of residential, commercial and industrial buildings from flood in the LGA is 13 per cent under a RCP 4.5 scenario. This accounts for a low probability of occurring but a high financial cost consequence of earthquake activity.

Actions taken or proposed:

- No actions have been taken or proposed for to address risks arising from an earthquake by Council within the region.

Climate Change Data Summary

Heatwave – measured by number of days with temperatures greater than 35°C

Heatwaves are a critical climate hazard affecting health, infrastructure, and ecosystems. Heatwave risk can be measured by tracking the number of days per year with maximum temperatures exceeding 35°C. This analysis, undertaken by Risk Frontiers in 2021, drew on 20-year averages from historical climate reanalysis data and future climate model projections under a ‘medium’ emissions scenario, represented by RCP4.5 (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2 – Frequency of days per year with temperature greater than 35 Celsius Degrees

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario.)

The data highlights how the frequency and seasonality of high-temperature events are expected to shift over time in the LGA, informing the need for climate adaptation in infrastructure, health, and planning decisions.

Key Findings:

- The magnitude of temperature extremes and frequency of hot days will increase for inland LGAs however, the Snowy Valleys will experience this change, but not the extent of the surrounding LGAs

- largest increases in heatwave and high temperature extremes will be seen during the summer months

- high temperature extremes will also occur more frequently during spring and autumn.

- Snowy Valleys will have less frequent cold nights which will become more apparent by 2070 with the frequency of frost nights dropping significantly (as seen in Figure 3 below).

Drought – measured by Keetch-Byram Drought Index, soil moisture and annual precipitation

Drought is a complex hazard influenced by temperature, rainfall, and how water is retained in the landscape. To assess how drought conditions are projected to change in the LGA, this analysis undertaken by Risk Frontiers in 2021 used three key climate indicators:

- Keetch-Byram Drought Index (KBDI) – a widely used index that estimates how dry the landscape is based on temperature and rainfall. It also reflects the flammability of surface fuels and is commonly used for fire management (see Figure 4 below);

- Soil moisture percentiles – a direct measure of how much water is retained in the soil compared to long-term conditions. Soil moisture is essential for agriculture, vegetation health, and ecosystem resilience (see Figure 5 below); and

- Total annual precipitation – tracks overall rainfall trends, which are a key input for drought but must be considered alongside evaporation and temperature to understand drought risk fully (see Figure6 below).

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

In summary:

- inland LGAs are more exposed and susceptible to drought. Snowy Valleys is no exception however, the effects will be less than the surrounding LGAs; and

- Under future climate, by 2070 the magnitude of drought will increase across all LGAs.

Figure 5: Annual mean soil moisture percentiles; values are calculated relative to present day climate, hence the 50% values for present day. Low values at 2070 are indicative of a drying landscape

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

Figure 6: Total annual precipitation in mm per year

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

These indicators are derived from climate model simulations using 20-year averages for present-day and future scenarios under RCP4.5. Together, they provide a fuller picture of both short-term and long-term drought potential, capturing the interplay between rainfall, heat, and water retention in the landscape.

Key Findings:

- By 2070 the magnitude of drought will increase across the Council area as soil moisture declines by 2070, with the greatest impact occurring during the winter and spring;

- changes in total annual rainfall are less than the projected changes in soil moisture and drought, suggesting that the increase in drought is being driven primarily by increasing temperatures and their effect on evapotranspiration; and

- Total annual precipitation is projected to dramatically decline by 2070 in the Snowy Valleys region.

Bush and grassfire – measured by the annual maximum Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI)

Bushfires and grassfires are among the most dangerous and disruptive climate-related hazards in South-East NSW Region. The annual maximum Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) is the nationally recognised measure for assessing bushfire danger and is widely used by emergency services to guide fire warnings, restrictions, and preparedness. FFDI is a composite index that incorporates temperature, wind speed, humidity, and recent rainfall to estimate how dangerous fire weather is on a given day.

This analysis undertaken by Risk Frontiers in 2021 used 20-year averages from historical reanalysis data and future climate projections under the RCP4.5 scenario (see Figure 7 below). This indicator helps identify trends in both the severity and seasonal timing of fire weather across the LGA.

Figure 7 – Magnitude of bushfire weather severity as represented by the annual maximum FFDI

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

Key Findings:

- the frequency of dangerous bushfire weather days and the magnitude of bushfire weather extremes will increase in the surrounding LGAs;

- the slower rate of increase for Snowy Valleys may be due to the influence of overall lower temperatures at higher elevations; and

- the largest changes for bushfire weather across southeast Australia are expected to be occurring during the spring, with a projected earlier onset of the bushfire season under a warmer climate.

Extreme rainfall and flooding – measured by daily precipitation over 30mm

Flooding poses a significant hazard to infrastructure, communities, and emergency services. This analysis uses the frequency of very heavy rainfall days (daily rainfall greater than 30mm) as an indicator of flood risk. This threshold (i.e., days with more than 30mm of rain often) is a recognised benchmark in climate and hydrological studies to identify rainfall events that can overwhelm stormwater systems, trigger flash flooding, and lead to significant overland flow.

Projections done by Risk Frontiers in 2021 compared 20-year averages for present day conditions with those for 2030 and 2070 under the RCP4.5 scenario (see Figure 8 below). This helps to understand how the intensity of rainfall events changes, which is crucial for flood management, infrastructure design, and emergency planning.

Figure 8: Frequency of very heavy rainfall days (>30mm)

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

Key Findings:

- the primary driver of year-to-year variability in rainfall will continue to be the tropical climate drivers of Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Inter-decadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). Projections for Pacific climate are indicating an increase in ENSO amplitude, meaning both El Niño and La Niña events will be stronger;

- extreme rainfall events will produce higher rainfall totals due to the physical relationship between a warmer temperatures and higher atmospheric moisture capacity; and

- higher rainfall totals may lead to higher flood levels during flooding events, but the frequency of these events will not differ significantly from present.

Severe storm, wind and hail

Severe storms, ranging from East Coast Lows to thunderstorms and hail events, pose a recurring hazard to communities and infrastructure. This analysis uses two key indicators to evaluate storm-related risk under a changing climate:

- frequency of East Coast Low (ECL) days – ECLs are among the most damaging storm systems affecting the region, often associated with extreme winds, heavy rainfall, large waves, and coastal erosion. Tracking their frequency is important for understanding long-term storm risks (see Figure 9 below); and

- annual maximum windspeed – is used to assess the strength of storm systems and frontal weather events that can bring down trees, damage infrastructure, and increase fire danger (see Figure 10 below).

Figure 9: Frequency of east coast low days

(Values are 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario)

Figure 10 – Annual maximum windspeed (km/hr).

(Values are averaged across each LGA and calculated as 20-year averages for present day climate and change for future climate under the RCP4.5 scenario—windspeeds at individual locations and years will be significantly higher than the averages)

These indicators help assess changes in both the occurrence and severity of damaging weather systems.

Projections done by Risk Frontiers in 2021 were based on 20-year averages comparing present-day conditions with future scenarios for 2050 and 2070 under RCP4.5. This helps identify trends in the intensity and potential impacts of storm systems in the LGA which may influence risk planning, emergency management, and infrastructure resilience.

Key Findings:

- Under present day climate, the Council area is exposed to several types of storms, including east coast lows (ECL), extra-tropical lows, fronts, snowstorms, thunderstorms, and hailstorms;

- ECL are one of the most damaging storm types to impact the Council area. ECL frequency is expected to increase slightly under future climate which is consistent with an expectation of increased large scale interactions between warm and cool air masses as the climate warms;

- storms tend to be more frequent during La Niña events and less frequent during El Niño events. This relationship is not expected to change under a warming climate.

- extratropical lows and associated fronts and thunderstorms can cause significant risk, especially during summertime when they are a primary cause of dangerous bushfire weather; and

- maximum annual windspeed is projected to increase across the Council area, suggesting an increase in the strength of frontal systems, especially in the Kosciuszko area.

NarCLIM 2.0 findings for Snowy Valleys Council

In 2022 NARClim 2.0 climate data was publicly released – this is the most up-to-date regional climate modelling available for NSW and ACT and is used Government planning, assessments, and strategies.

Table 2 below describes the anticipated future climate projections specific to Snowy Valleys Council based on NARCLiM 2.0 RCP4.5 (medium emissions) and RCP8.5 (high emissions) scenarios.

This information can be viewed through can be interactive climate change project map via https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/projections-map

Table 2: Future climate predictions for Snowy Valleys Council

Risk Exposure Summary

Hazards

A hazard is a natural process or occurrence, a source event which has the potential to result in harm or cause loss or damage depending on exposure. The South Eastern Regional Emergency Management Plan has identified the following hazards as having risk of causing loss of life, property, utilities, services and/or the community’s ability to function within its normal capacity:

|

|

|

In 2024, the NSW State Disaster Mitigation Plan identifies these additional 3 hazards having the same risk to life and property: 44

- Coastal hazard (erosion and inundation);

- Storms and cyclones; and

- Tsunami.

Climate modelling helps us to examine the implications for hazard likelihood. The Climate modelling performed by Risk Frontiers as part of the Resilience Blueprint found that Snowy Valleys has:

- low flood hazard risk with 4.03% of the land within a modelled floodplain. This follows Tumut River in from the north and Tooma and Swampy Plain Rivers from the west (see Figure 11 below); and

- medium bush and grassfire hazard risk with a modelled annual burning probability of 0.71%. This risk area is largely concentrated in the Kosciuszko National Park and the other vegetated areas in the east (see Figure 12 below).

Figure 11: Snowy Valleys Flood Hazard Index

A dark blue indicates a flood plain, the lighter colour out of it.

The flood hazard index uses a map of modelled flood plains identified by several geographical/geospatial variables including different river types, river stream order, distance to river network, land cover, soil type, average slopes in known flood areas, relative changes in elevation near rivers, and river basin characteristics.

Figure 12: Snowy Valleys Bushfire Hazard

Life, Property, Economic and Environmental Loss Risk

Fatalities and life loss

As shown in Figure 13 below, the risk that is posed to life is very difficult but a reality to of natural hazards. From a human health perspective, life loss throughout the region from 1900 to 30 June 2020 has been analysed using PerilAUS, Risk Frontiers’ database of natural hazard impacts. The analysis found that in the Snow Valleys, floods have resulted in the most fatalities – 7 fatalities, followed by bushfire (6 fatalities), lightning (3 fatality), and landslide (1 fatality).

Despite the above, more lives have been lost as a result of the impacts of disaster events across the Snowy Valleys Region in the days, weeks, months and years that follow. The physical and mental health toll of events is enormous. It also does not capture cascading health issues and fatalities. Data in these regards is difficult to bring together but does not change the reality of the pervasive impact of disasters.

Figure 13: Snowy Valleys Fatalities from Natural Hazard

Impact on Property and Infrastructure

In terms of the risks posed to property and infrastructure, Risk Frontiers’ Natural Catastrophe loss models have been used to estimate the financial cost, or Average Annual Loss (AAL) across four key hazards in the Council being bushfire, flood, hailstorm and earthquake. The models evaluated losses for commercial, residential and industrial properties.

Under current conditions, the overall baseline AAL for the Snowy Valleys is approximately $1 million and the analysis found that hail is the most significant natural hazard accounting for 54% of the AAL, followed by earthquake (23%) and bushfire (14%) as shown in Figure 14 below.

Figure 14: Distribution of the Average Annual Loss (AAL) of infrastructure by hazard for the Snowy Valleys

Average Annual Loss identified in the State Disaster Mitigation Plan

Snowy Valleys Council is identified as being within the top 3 LGAs in NSW with the highest level of natural environment risk from earthquakes (with Upper Lachlan Shire having the second highest and Snowy Monaro Council with the third highest). This means the LGA has a high risk of ruptures and fissures – deformations or openings in the earth’s surface, displacement of soil and/or rocks including landslides, and liquefaction of soil in coastal, estuarine and riverine areas.

Additionally, the indicates that the AAL in Snowy Valleys Council for built environment in 2023 consisted of the following:

- Coastal hazard (erosion and inundation) – Very Low;

- Storms – Low;

- Cyclones – Very Low; and

- Tsunami – not recorded but noted as a rare event.

Editors note: the SDMP does not include specific AAL per LGA. It is colour coded on a scale from $0m to $112m.

Environmental Loss Risk

Risks to threatened flora, fauna and ecological communities from fire and flood were analysed using the following values:

|

|

|

The fire and flood indices were overlaid with an exposure index locating threatened flora, fauna and ecosystems along with agricultural lands. The analysis found that there are:

- Fauna exposure is medium. There are 27 different vulnerable animal species in the region, of which 13 are vulnerable, 8 are endangered, and 6 are critically endangered.;

- Flora exposure is medium/high. There are 26 different vulnerable plant species in the region, of which 17 are vulnerable, 4 are endangered and 5 are critically endangered; and

- Ecological community exposure is high. There are 4 different vulnerable ecological communities in the region, of which 2 are endangered and 2 are critically endangered.

- The analysis also that the natural environment encompasses 61.04% of the region (45.28% of which is protected), 22.49% devoted to agriculture and farming and the remaining 16.47% is developed built environment.

- The total maximum above ground biomass (indicating the potential vegetation density the LGA could support) is moderate with 16,412 tonnes of dry matter over the LGA. The overall exposure of the Snowy Valley’s environment has medium as seen in Figure 15 below.

Agricultural Productivity

While there are no significant changes for rainfall, worsening drought conditions associated with warming temperatures will directly lead to lower overall soil moisture as seen in Table 1. A projected decrease in soil moisture from a warmer climate may impact beef and overall agricultural productivity in the Snowy Valleys.

There is a correlation between agricultural productivity and climate parameters representing temperature and hydroclimate variability. Productivity of beef and sheep operations tends to be higher during years that are wetter and cooler years with retained soil moisture, and low risk of consecutive dry days. This correlation is particularly significant for sheep, but not as significant for beef however, there are there are sensitivities to hot days and drought conditions as shown in Figure 16 below.

There are currently no data available on how climate parameters may affect fruit production at the time of writing.

Figure 16: Correlation between Agricultural Operations and Climate Parameters in Snowy Valley

Vulnerability and Capacity

Resilience is generally regarded as a function of the intersection of relative exposure, social vulnerability and community capacity:

- Relative exposure is a function of hazard, describing the frequency and magnitude of natural hazard events and capturing the compounding effect of multiple hazards (fire and flood for this analysis);

- Physical exposure of a community is determined such that the quantum of exposed people, buildings, essential facilities, industry, and agriculture can be evaluated;

- Social vulnerability is determined by examining socio-economic and demographic factors that may exacerbate or ameliorate the effects of an external threat to a person’s life, livelihood, or assets; and

- Community capacity to resist, avoid and / or adapt to a disaster and to use these abilities to create security either before or after a disaster can be determined by examining several factors.

For each of these measurement framework indicators, an index has been produced by a weighted average of each metric contributing to the category. An analysis of the measurement framework indicators for each Statistical Area 1 (SA1) across South East NSW culminates as an integrated index of resilience; Figure 17 and Figure 18 shows community resilience indices for the Snowy Valleys.

In the Snowy Valleys:

- the mean relative exposure component of the resilience index is average for bush/grass fire and high/extremely high for flood. There are no SA1s scoring low to extremely low for either resilience to bush/grass fire or flood in the Scow Valleys (see Figure 19 and Figure 20 below);

- There are no SA1s scoring low to extremely low for the relative exposure component of resilience to either bush/grass fire or flood;

- The Council area’s mean social vulnerability score is low. 56.4% of the population reside in SA1s scoring low or worse for the social vulnerability component of resilience (see Figure 21 below); and

- The mean community capacity component of the resilience index is high average for both bush/grass fire and flood (see Figure 22 and Figure 23 below).

Gaps in Data

While this local profile is underpinned by robust regional data and hazard modelling, several key data gaps remain that limit the precision of localised risk reduction planning:

- Community preparedness and capacity indicators: No recent community survey data exists on disaster readiness, access to emergency plans, or levels of volunteering in disaster response organisations.

- Historical event records: Detailed local records on the frequency, impacts, and recovery costs of past snow, storm, hail, and earthquake events are limited or not centralised.

- Economic disruption data: There is insufficient insight into how previous disasters have impacted the local economy, particularly small businesses, tourism, and agricultural supply chains.

- Infrastructure interdependencies: Modelling on critical infrastructure interdependencies (e.g., how flood risk to roads affects emergency access or supply deliveries) is not available at the LGA level.

- Monitoring and evaluation systems: Council currently lacks a framework to consistently track resilience outcomes over time, including climate impact monitoring and post-disaster recovery effectiveness.

- Integration of hazard overlays into planning instruments: While hazard data exists (e.g., fire and flood overlays), there is limited evidence that these are fully embedded within the Local Environmental Plan (LEP) or Development Control Plan (DCP), limiting the effectiveness of risk-informed development controls.

- Local flood sub-plan: Council, in association with the NSW SES, have not undertaken a Volume 2 of a local flooding emergency sub plan. Flood studies are currently being undertaken by Council, however, the extent of flood prone land in the major settlements in the Snowy Valley Region has not yet been accurately discerned.

Reference

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: About the profile areas’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/about?WebID=160

- Department of Regional NSW, 2023, ‘ Snowy Valleys Regional Economic Development Strategy –2023 Update’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/reports-amp-strategies/snowy-valleys-reds-2023-update-final-2.pdf

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: About the profile areas’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/about?WebID=160

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: Population and dwellings’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/population?WebID=160

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: Five year age groups’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/five-year-age-groups?WebID=160

- Ibid.

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: Need for assistance’. Available online athttps://profile.id.com.au/crjo/assistance?WebID=160

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: Overseas arrivals’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/overseas-arrivals?WebID=160

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: Language used at home’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/language?WebID=160

- Ibid.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023, ‘Region summary: Snowy Valleys’. Available online at https://dbr.abs.gov.au/region.html?lyr=lga&rgn=17080

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021, ‘Snowy Valleys: 2021 Census All persons Quickstats’. Available online at https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA17080

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021, ‘Snowy Valleys: 2021 Census All persons Quickstats’. Available online at https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA17080

- Department of Regional NSW, 2023, ‘Snowy Valleys Regional Economic Development Strategy –2023 Update’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/reports-amp-strategies/snowy-valleys-reds-2023-update-final-2.pdf

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: About the profile areas’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/about?WebID=160

- Snowy Valleys Bush Fire Management Committee, 2017, ‘Bush Fire Management Plan’. Available online at https://www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/91875/SnowyValleys_BFRMP_20180110.pdf

- Ibid.

- .id consulting, 2025, ‘Snowy Valleys Council: About the profile areas’. Available online at https://profile.id.com.au/crjo/about?WebID=160

- Snowy Valleys Council, 2025, ‘Your Councillors’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/Council/About-SVC/Your-Councillors

- Department of Regional NSW, 2023, ‘ Snowy Valleys Regional Economic Development Strategy –2023 Update’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/reports-amp-strategies/snowy-valleys-reds-2023-update-final-2.pdf

- Snowy Valleys Bush Fire Management Committee, 2017, ‘Bush Fire Management Plan’. Available online at https://www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/91875/SnowyValleys_BFRMP_20180110.pdf

- Snowy Valleys Council, 2020, ‘Submission to the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/general-documents/submission-to-the-royal-commission-into-national-natural-disaster-arrangements.pdf

- Lyall & Associates Pty Ltd and Nexus Environment Planning Pty Ltd, 2018, ‘Adeling Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan’. Available online at https://flooddata.ses.nsw.gov.au/dataset/adelong-floodplain-risk-management-study-and-plan-report

- ABC News, 2010, ‘Major floods hit Tumut and Upper Murray’. Available online at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-03-02/new-document/3864264

- ABC News, 2010, ‘Residents flee as creek bursts banks’. Available online at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-10-16/residents-flee-as-creek-bursts-banks/2300224

- ABC News, 2020, ‘Flash flood hits Tumbarumba in NSW, forcing evacuation of home and caravan park’. Available online at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-24/tumbarumba-storm-rescue-and-nsw-weather-warning/12810474

- Hume & Hovell Track, (n.d.), ‘Col Daniel Bridge wiped out’. Available online at https://www.humeandhovelltrack.com.au/track-updates/col-daniel-bridge

32.

- Lyall & Associates Pty Ltd and Nexus Environment Planning Pty Ltd, 2018, ‘Adeling Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan’. Available online at https://flooddata.ses.nsw.gov.au/dataset/adelong-floodplain-risk-management-study-and-plan-report

- Snowy Valleys Council, 2025, ‘Community Experiences Sought for Brungle Flood Study’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/News-Media/Community-Experiences-Sought-for-Brungle-Flood-Study

- Snowy Valleys Council, 2025, ‘Council Keen to Hear About Flooding Events’. Avialalble online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/News-Media/Council-Keen-to-Hear-About-Flooding-Events

- Snowy Valleys Council, 2025, ‘Community Experiences Sought for Tumbarumba Flood Study’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/News-Media/Community-Experiences-Sought-for-Tumbarumba-Flood-Study

- Department of Home Affairs, 2025, ‘Disaster Assist: NSW Snowy Valleys Storms (From 25 November 2024)’. Available online at https://www.disasterassist.gov.au/Pages/disasters/new-south-wales/nsw-snowy-valleys-storms-25112024.aspx

- Department of Regional NSW, 2023, ‘ Snowy Valleys Regional Economic Development Strategy –2023 Update’. Available online at https://www.snowyvalleys.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/reports-amp-strategies/snowy-valleys-reds-2023-update-final-2.pdf

- ABC News, 2010, ‘Hail-hit Batlow declared disaster area’. Available online at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-11-14/hail-hit-batlow-declared-disaster-area/3664408?source=rss

- NSW Reconstruction Authority, 2024, State Disaster Mitigation Plan 2024-2026. Available online https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2024-02/State_Disaster_Mitigation_Plan_Full_Version_0.pdf

- NSW Ambulance, 2024, ‘State Heatwave Sub Plan’. Available online at https://www.nsw.gov.au/rescue-and-emergency-management/sub-plans/heatwave

- Marion Leiba (Geoscience Australia), 2007, ‘Earthquakes in the Canberra Region’. Available online at https://www.ga.gov.au/bigobj/GA11006.pdf

- South Eastern Regional Emergency Management Committee, 2021, ‘South Eastern Emergency Management Plan’ (updated October 2023). Available online at https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2023-10/South_East_Region_EMPLAN_v2.1.pdf

- NSW Reconstruction Authority, 2024, ‘State Disaster Mitigation Plan 2024-2026’. Available online https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2024-02/State_Disaster_Mitigation_Plan_Full_Version_0.pdf